Osteoarthritis (OA) is a scary word. It can lead many active people to think they have to give up their lifestyle and hobbies because of the “wear and tear” it is causing on their knee or hip.

For young active people who have surgery, particularly a knee surgery, doctors often emphasize a fear of early onset osteoarthritis that will lead you to get a knee replacement early in life. Unfortunately, this emphasis on preventing osteoarthritis all too often focuses on avoiding irritating activities rather than improving your ability to perform these activities without them becoming irritating. This article will explain what osteoarthritis is and why exercise is helpful rather than hurtful.

What is Osteoarthritis & What Joints Does it Affect?

Osteoarthritis is the wearing away of the protective cartilage layer inside your joint. It is most common in weight-bearing joints like the knee and hip and is normal as we age.

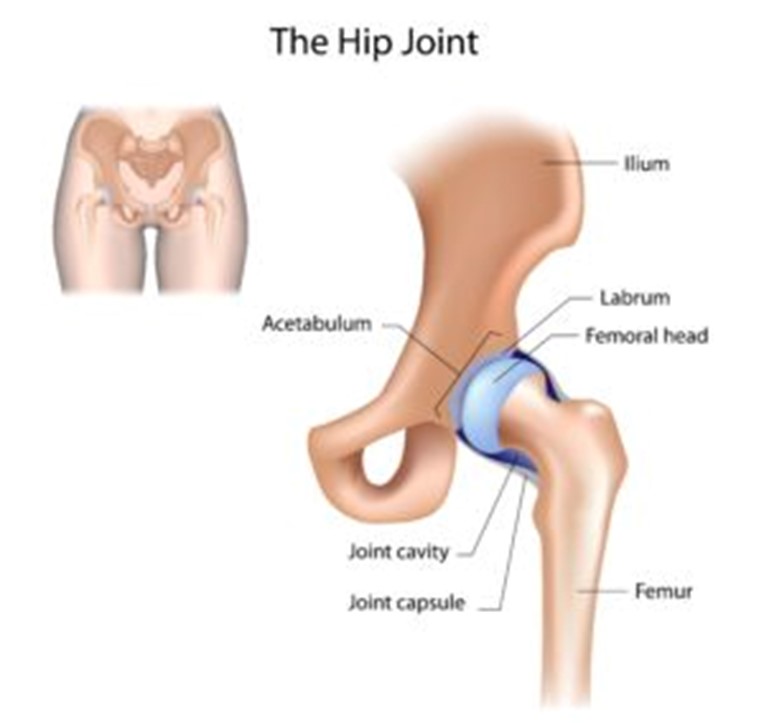

Your hip joint (femoroacetabular joint) is a ball-in-socket where the ball of your thigh (femur) fits into the socket of your pelvis (acetabulum). Both ball and socket are surrounded and protected by a smooth layer of hyaline cartilage. Your acetabulum also has an additional ring of cartilage called a labrum which helps to stabilize and support that hip joint.

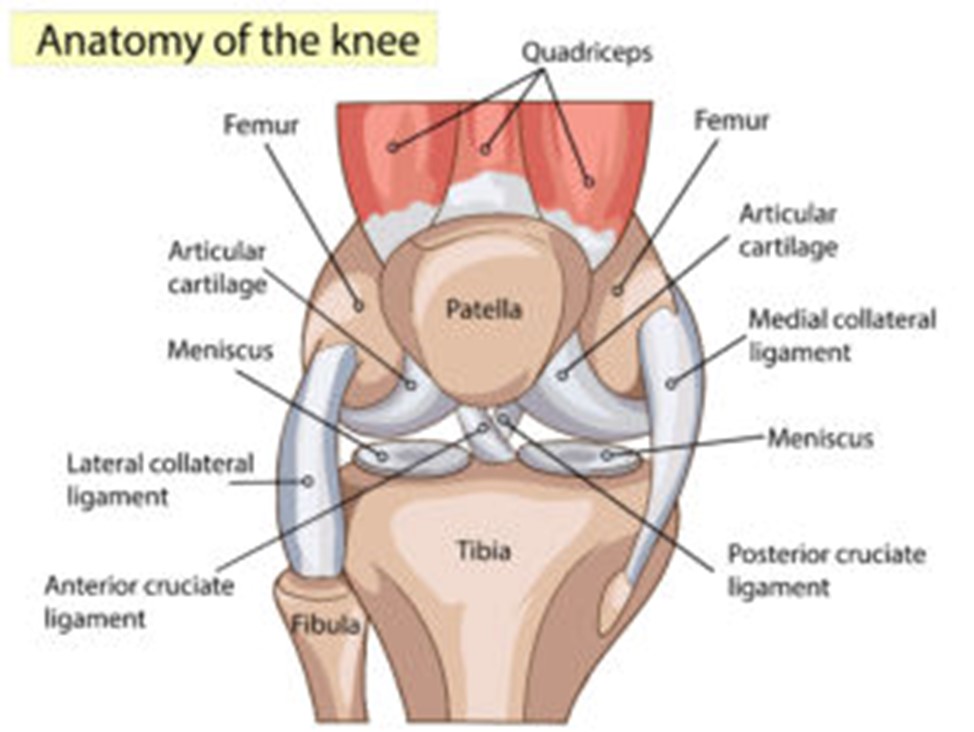

Your knee joint (tibiofemoral joint) is made of your thigh bone (femur) and shin bone (tibia). These joints are further separated by your medial and lateral menisci, which serve as an additional layer of shock absorption and protection for your cartilage.

Osteoarthritis in these joints occurs when the cartilage has started to wear away and areas of bone are contacting each other directly. This process can be accelerated by damage to the labrum in the hip and damage to the menisci and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in the knee. This sounds painful, however up to 43% of asymptomatic (having no signs or symptoms) individuals over the age of 40 years old showed signs of osteoarthritis on MRI scans, these numbers increased even further with an increase in age.

That means that your average 50-year-old that is walking around without an ounce of pain had nearly a 50% chance of having signs of osteoarthritis on an MRI. Similar findings are common for both hip labral tears and meniscus tears. Many people have them and don’t have pain. It is important to consider that you are not your MRI, and the presence of structural damage does not indicate pain, symptoms, or future disability. A variety of factors contribute to the difference between developing OA and developing pain and disability One of the biggest contributing factors is strength.

Can Strength & Exercise Help My Osteoarthritis?

Yes! There is a mountain of evidence that shows that an 8-week course of strength training was as effective in reducing the symptoms of knee OA as 4 saline injections. In fact, studies show that in those with knee OA, improving quadriceps strength led to a significant improvement in their knee pain and physical function. Not only can quadriceps strength help limit the development of symptomatic OA and help decrease your pain and improve your function if you already have OA but it may even be able to prevent you from developing OA. Studies have shown that in both men and women, maintaining higher quadriceps strength is one of the most effective methods of preventing the development of knee OA

If OA is a problem with your bones, joints, and cartilage how can your muscle prevent this? Your muscles provide shock absorption for your bones and joints. The stronger your muscles are, the less impact that is going through that joint.

Conclusion

Improving muscle strength through exercise is one of the best ways to prevent the development of osteoarthritis. Furthermore, for an individual with osteoarthritis, improving their strength is one of the best ways to improve their symptoms and function.

References

Culvenor AG, Øiestad BE, Hart HF, Stefanik JJ, Guermazi A, Crossley KM. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis features on magnetic resonance imaging in asymptomatic uninjured adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(20):1268-127

Muraki S, Oka H, Akune T, Mabuchi A, En-yo Y, Yoshida M, et al. Prevalence of radiographic knee osteoarthritis and its association with knee pain in the elderly of Japanese population-based cohorts: The ROAD study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:1137–4

Muraki, S., Akune, T., Teraguchi, M. et al.Quadriceps muscle strength, radiographic knee osteoarthritis and knee pain: the ROAD study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 16, 305 (2015).

Bandak E, Christensen R, Overgaard A, et al. Exercise and education versus saline injections for knee osteoarthritis: a randomised controlled equivalence trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(4):537-543. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221129

Amin S, Baker K, Niu J, Clancy M, Goggins J, Guermazi A, Grigoryan M, Hunter DJ, Felson DT. Quadriceps strength and the risk of cartilage loss and symptom progression in knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Jan;60(1):189-98. doi: 10.1002/art.24182.

Takagi S, Omori G, Koga H, et al. Quadriceps muscle weakness is related to increased risk of radiographic knee OA but not its progression in both women and men: the Matsudai Knee Osteoarthritis Survey. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(9):2607-

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Management of Osteoarthritis of the Knee (NonArthroplasty) Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline. https://www.aaos.org/oak3cpg Published 08/31/2021