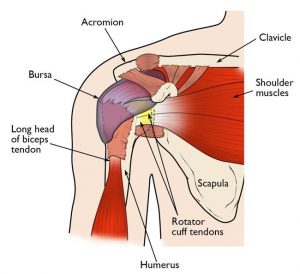

The rotator cuff Is a group of four muscles which include the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis and teres minor muscles. Their primary role is to stabilise the shoulder in its range of motion. As the shoulder is a ball and socket joint, it sacrifices stability for its extreme range of motion, therefore the rotator cuff’s role is to provide a compressive and downward force at the glenohumeral joint, in order to keep the head of the humerus within the glenoid fossa (keeping the ball sitting in its socket). Without this force, the head of the humerus will shift upwards and compress the subacromial space (the space between the glenohumeral joint and the below the acromion, the top-most bone of the shoulder).

In this subacromial space lies important structures including the supraspinatus tendon, biceps long head tendon and subacromial bursa. The rotator cuff muscles maintain this space via stabilising the glenohumeral joint through the shoulder’s range of motion. A rotator cuff injury occurs when there is damage to the muscle or tendon associated with either the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis and teres minor muscles. Quite often, the rotator cuff muscles or tendons will be injured for various reasons such as overuse in overhead activities, poor shoulder mechanics and scapular control or weakness. Consequently, the ball and socket joint of the shoulder can become unstable and can cause compression of the subacromial space.

As a result, the structures inside can be impacted which can lead to inflammation, pain, or an injury. A rotator cuff injury can lead to pain, which can inhibit the rotator cuff muscles from activating and doing their job. Typical symptoms for a rotator cuff injury or impingement include the following.

- shoulder pain in the front and back of the shoulder

- pain or weakness with overhead activities and lifting your arm to shoulder.

- Poor shoulder setting and scapular control (seen by hitching of the shoulder and internal rotation of the shoulder)

- Impingement symptoms due to excessive upward movement of the humeral head and compression of the subacromial space.

So, how can exercise help? Rotator cuff strains and tears respond well with conservative management in the form of exercise and providing education on how to manage pain and to modify daily activities to reduce load on the shoulder. By seeing an exercise physiologist, they will be to do the following;

- Identify and correct poor shoulder mechanics that contribute to increasing upward shearing force and compressing the sub acromial space (e.g when the shoulder is elevated or internally rotated due to tight pectoral or upper trapezius muscles, all of the rotator cuff has to work against). Improving mechanics and teaching proper shoulder setting will open the sub acromial space, allowing proper motion of the humeral head in the shoulder joint, placing much less stress on the rotator cuff muscles.

- Provide an individualised program that will Improve the activation and strength of the rotator cuff muscles, so that they can of the shoulder joint in external and internal rotation, and shoulder abduction and provide compressive and downward shear forces.